Insects have great potential to serve as a sustainable food source owing to their notable nutritional value, high feed conversion rate, and low environmental footprint. The sharing of well-established recipes in cultures where insect consumption is normalized can facilitate new product development among cultures where consumption is resisted. In this project, we traveled to both rural and urban areas of Oaxaca, Mexico and studied the collection, processing, retailing, and eating practices of edible insects such as chapulines, chicatanas, maguey worms, and cochineal.

Collection of insects

The collection of both chapulines and chicatanas requires an understanding of the time in which they are most abundant. Chicatanas are only available after the first rains of the rainy season (occurring around the beginning of June) when their nests burst and the ants fly around the area, allowing for people to gather, collect, and consume them. Chapulín collection typically occurs during the rainy season in spring through the early winters (May-October).

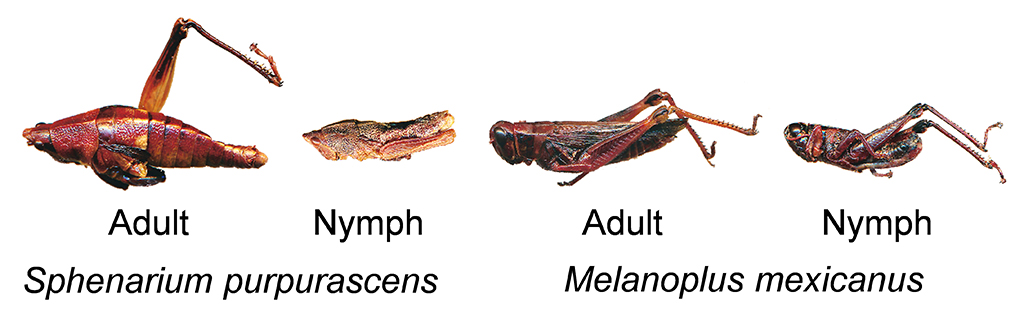

Maestra Angelina and Señor Bacedelis, two members of an indigenous Mixtec community in Ixpantepec Nieves, recounted stories of collecting chapulines in June or early October/November, respectively. Different stages of chapulines are collected in different seasons. According to a woman from the regional market of Tlacolula, chapulines are generally captured on a farmer’s land – either in the alfalfa fields or in the milpa, a field where corn, bean, and squash are interplanted. Her husband collects the chapulines nymphs from the alfalfa, while the adults are generally found in the milpa. The nymphsare found in the alfalfa fields where they hatch and feed off the tender leaves. As they age, the adultsleave the alfalfa to the open fields of the milpa, where these insects sunbathe and feed along the stocks of corns and the leaves of squash. An interesting observation we made is that the chapulines sold in the market are a mix of at least two different species, S. purpurascens and M. mexicanus, and the proportions of the two species in nymph versus adult populations are quite different. M. mexicanus (83%) are the predominant species in nymph chapulines, while S. purpurascens (65%) are more abundant in adults. This may indicate that these species have different hosts at different life cycle stages.

Chicatana collection, according to Maestra Angelina and Doña Adelina, generally occurs during June for only one to two days. The queens and drones of chicatana ants are collected for consumption. These alates are quite large. They come out of their nests to mate after the first major rains of the year. People in the community track the movement of their nests and know where to harvest them in the fields and along the roadways. During the season, people check the nests regularly to determine when they might emerge to feed, mate, and begin the establishment of new nests. The entrances of the nests, usually covered up with dirt to form a pile similar to subterranean termites, open up when they are about to come out. According to Don Juan, the worker ants may seal up the entrances after the queens and drones are gone and open new entrances somewhere else. Local residents track the new nests by following the workers as they bring leaves back to the nests.

Insects are poikilothermic animals that remain inactive when the temperature is low. Chapulín capture requires these insects to be sufficiently cooled so that they are easy to capture; once the temperature increases they tend to be too active and are difficult to capture. Thus, chapulín gathering is done in the early morning, shortly after sunrise. People walk through their alfalfa or milpa fields scooping up chapulines with their nets and subsequently place them in buckets with lids for later preparation. Doña Adelina reported that she is able to fill a two-liter bucket each morning that she harvests chapulines.

A very similar timetable exists for the gathering of chicatanas asonce they start emerging from their nests and are warmed by the sun, they increase their speed and agility. Chicatanas are alates, making their movements more difficult to control. Doña Adelina explained that she and her children wake up at 3 a.m. around the time of the first rainfalls of the season to pick a spot near their ‘designated’ ant nest to prepare themselves for the chicatanas to emerge. Each nest has many entrances and the most prolific gathering occurs when someone is stationed at each entrance/exit. Family or friends often go together to collect the ants and then share the harvest. One technique to slow the ants down and prevent them from flying away is to cover the entrances with tree leaves and twigs. Another technique is to cover the nest with a net. Many people described chicatana capture as a dance, in which one hastily snatches chicatanas left and right while hopping about in order to prevent the ants from climbing up their legs as their sharp bites are painful . Doña Adelina acknowledges the painful bites, but she bears through the pain in order to get the nourishment and income she needs for her family. She does not wear any gloves because she does not want her fingers ‘to slip’ as she captures each chicatana; she does, however, wear tall rubber boots to protect her legs and feet. Maestra Angelina recounted her chicatana collection experiences as a child being ‘painful’ and ‘tearful’ because the bites had hurt her so much. While in general, insect foraging is not based in gendered labor, many of our participants noted that the painful bite pushed more men toward collection while women processed the captured ants for consumption. In just a couple of hours, two to three people can collect five liters of chicatanas.

Both chapulines and chicatanas are fasted for one to three days in bags prior to processing, in which these insects empty their intestinal tracks to allow for any waste to leave their systems. As these insects are consumed with their gut microflora, the microbial hazards are a major food safety concern. However, the emptying of the gut content may not be effective in reducing the microbial numbers. Therefore, the subsequent thermal processing described by our participants is important in assuring healthy outcomes for consumers.

Processing and storage

The chapulines usually die naturally following the fasting period in the bags. They are then washed and sun-dried for about two days prior to cooking. To get to the finished product quicker, some people skip these steps and simply boil the chapulines in water until their color turns from green to red. There are three common flavors of chapulines in Oaxaca. They can be sautéed in oil and garlic and sold in the markets as naturales. Adding lime juice instead of the oil and adding more garlic and salt gives the chapulines a sour and salty taste. These ingredients not only contribute to the flavor, but also reduce the water activity and pH of the product and thus extend the shelf life. For example, the addition of lime juice and salt resulted in high moisture (36-41%) and ash (12-16%) contents with a low pH (3.67-4.01) of the insects. Chapulines cooked in chiles constitute the third variety sold in the marketplace. The chicatanas are toasted on a comal without any additional ingredients added. They are often toasted on a low-medium fire for 20-30 minutes until the texture becomes crunchy, and the wings fall off. Unprocessed chicatanas are also sold in the market. They can be easily identified by the presence of wings. However, vendors often negotiate with chicatana collectors to sell them at a lower price when wings are still attached because this is more work for the vendors when they need to process them before selling.

According to Maestra Angelina, the processed insects can be stored at room temperature for two months, refrigerated for four months, or frozen for a year before the flavor changes. This is due to the low pH values and water activities of the processed insects. For instance, the processed chicatanas and red maguey worms collected from the market had water activities below 0.6, indicating no microbial proliferation on these samples. The processed chapulines had a water activity range of 0.71-0.74, which limits the growth of pathogenic bacteria but not the xerophilic molds and osmophilic yeasts. However, with the low pH values, the chapulines are considered an intermediate-moisture food that has shelf stability of several months without thermal sterilization, nor freezing or refrigeration. Cochineal insects are processed quite differently. Once removed from the cactus, the insects die, and then are ground with a mortar and pestle into an immense red color. Combined with ash and various amounts of lime juice, a vibrant display of colors can be made that range from pink to magenta to a blood red in just a matter of seconds.